Amid conflict, insecurity, and climate change, East African countries are turning to data for solutions

Few countries have been more generous towards refugees than Uganda. Here, refugees have freedom of movement, the right to work and access to basic services.

Uganda is also at the forefront of statistical inclusion, that is, the inclusion of forcibly displaced people in national statistics. The country’s Demographic and Health Survey, which was released this month, found, for example, that refugee children are more likely to be underweight (12.1 percent) relative to the national average of 9.7 percent. Statistics like these are critical if governments are to provide adequate health, education and other basic services.

In East Africa, this is becoming the norm. Rwanda included refugees and stateless people in their national census and Kenya has included refugees in theirs. Djibouti is planning to include refugees and internally displaced people (IDPs) in their census while Somalia also plans to do the same for IDPS. But in these contexts, where conflict, insecurity, and climate change are major influences, the situation can change as fast as data is collected.

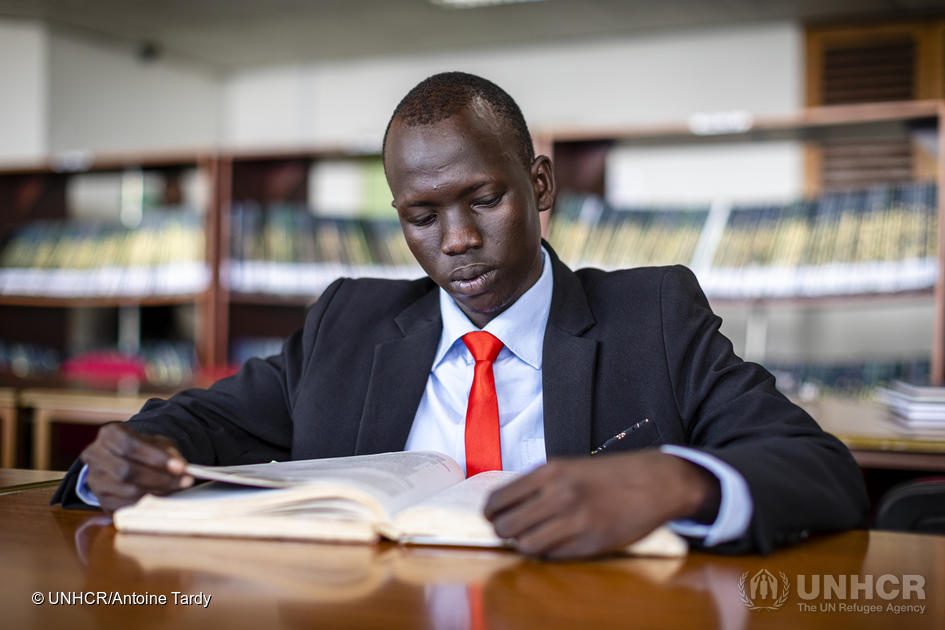

“I always dreamed of studying medicine and training as a surgeon or genetic engineer. When my grandmother died my mum said perhaps the doctors were not qualified enough or didn’t have the proper resources. I told myself if people die in such circumstances, I would do my best to help turn things around.”. South Sudanese refugee, Gabriel, is studying clinical medicine and community health at Clarke International University in Kampala, Uganda, a country where refugees have access to education at all levels.

To address this, in Somalia, the JDC funded a socioeconomic study of refugees, IDPs and host communities. Rapid monitoring found that increasing food insecurity and diminished livestock herds have devastated the traditional pastoralist economy. Hodan Osman Abdi, Somalia’s National Coordinator of Human Capital Development, was well aware of this when she attended the World Bank Fragility Forum in February. She stressed that people should not just be healthy but should also be able to contribute to the country which is why the government needs to ‘guide investments’.

South Sudan faces similar issues and, at the same time, has received over 600,000 of refugees from Sudan since April 2023. Faced with a polycrisis, it would be easy for any government to deprioritize data and focus on urgent needs. Yet data is vital to meet the needs of any population effectively. This is one of the reasons why UNHCR elected to conduct its first consolidated household survey – the Forced Displacement Survey (FDS) – in South Sudan. Designed to streamline and standardize its surveys of forcibly displaced people, the FDS collects demographic, civil, political, economic, social, and cultural data on refugees, asylum-seekers, and host communities, which is used for their protection.

Considering that more than one country in East Africa faces similar challenges, it is useful to examine the impact and characteristics of forced displacement across the region. This month’s JDC Digest does that and finds that researchers come to the same conclusion as Ms. Osman Abdi, namely, that self-reliance and mobility are the subject of growing bodies of work, with important policy implications. What creates good policy is a decent quality and quantity of data.

Yours sincerely,

Aissatou (Aisha) Dicko

Head of the World Bank-UNHCR Joint Data Center on Forced Displacement