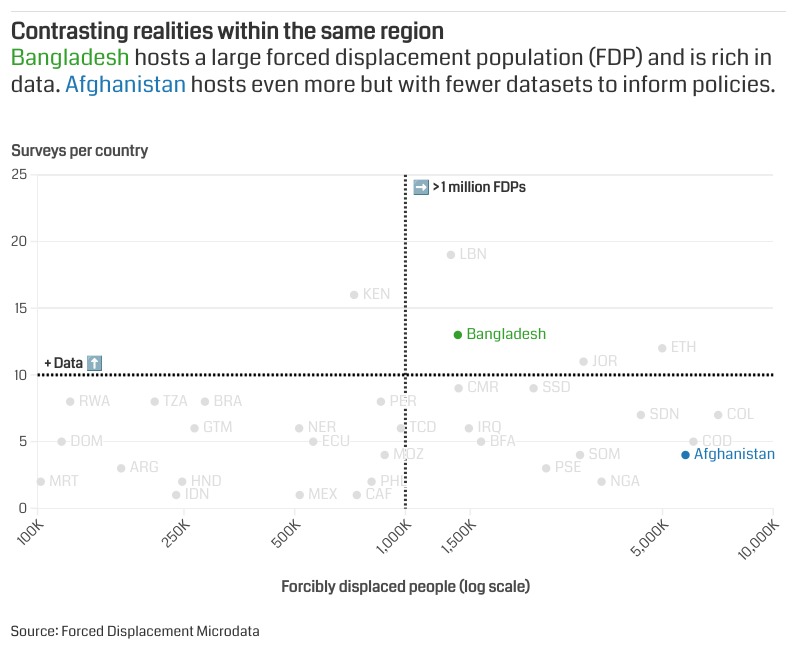

Data rich and data poor – Within the same region, Bangladesh and Afghanistan are vastly different data contexts

Data on forced displacement in Bangladesh and Afghanistan typifies the characteristics of forced displacement data globally. Bangladesh hosts a large refugee population and is rich in data, while Afghanistan, a country of origin for millions of refugees, has a scarcity of data about them.

Bangladesh has made strides in development in recent decades. Although the population has almost tripled in the last fifty years, nominal gross domestic product (GDP) increased by almost 5000 percent over the same period. By almost every development indicator – school enrollment, life expectancy, employment – Bangladesh has vastly improved. The current challenge for the country is equality; extending economic prosperity to refugees and others who have been excluded from the country’s success.

Hardship for refugees and hosts in Bangladesh was compounded during the COVID-19 pandemic. To determine how and the extent to which refugees were affected, the JDC supported studies on food security and employment in 2020. Both studies compared the situation of refugees, who currently number one million, with that of hosts, and found that those who were already vulnerable experienced even more hardship. Unemployment increased sharply, from 36 percent to 77 percent and there was evidence that daily and weekly wage workers suffered the most. However, programs, such as e-vouchers and fresh food corners, alleviated the worst of the situation.

In Afghanistan, the situation is far more daunting. After the United States’ withdrawal from the country in August 2021, almost all of the country’s socioeconomic indicators, including life expectancy, school attendance, employment and GDP, deteriorated. At the same time, there is little data available to gauge the overall welfare of the population and vulnerability of the poor for operations and for policymakers to determine what interventions are needed. Of the eleven summaries on Asia that are compiled in this month’s literature review, only one is about Afghanistan, despite the fact that the largest population of refugees in the world originates from that country.

This is the very reason that the JDC exists – to provide data on forcibly displaced populations that can inform policies and planning to reduce poverty. In response to the recent wave of returns to Afghanistan, the JDC funded a rapid needs assessment of returnees that was completed in May this year. The assessment found that returnees could face limited livelihood opportunities due to their lack of education – 94 percent have no formal education.

The assessment analyses the socioeconomic profile of returnees, by combining administrative records and existing household surveys. While this approach may not be applicable to many other displacements it is a unique way of generating data and analysis where data is scarce.

Applying innovative methods to obtain data is one of the JDC’s strategic pillars and a must if forcibly displaced people are to be included in policies and programs.

Aisha Asamusa is one of these statistics, but she is much more than a number. “Only if peace comes, will we go back,” she says, voicing the aspirations of 70 percent of Sudanese refugees in the country who are either waiting for the situation to improve, or do not intend to return. Aisha Asamusa is also a businesswoman. She constructed an oven and rents it out to people nearby to cook bread. The money she earns not only helps to support her family, but also others in her community. She belongs to a group of women who often pool their savings to help others when they are in need. Aisha’s entrepreneurial activities indicate the potential that she and refugees around her have for self-reliance.

The findings of UNHCR’s Forced Displacement Survey in South Sudan offer a detailed picture of Aisha’s life. She is a single parent in a country where almost half of refugee households are headed by women, and half of her six children are under 15 – the median age of a refugee in South Sudan. The other thing that is sadly typical about Aisha Asamusa is that her displacement is driven by conflict.

Data from UNHCR’s Global Trends clearly identifies conflict (measured by conflict fatalities) as the main driver of forced displacement. While the causes of conflict might be difficult to address, data can help countries affected by forced displacement to include and support people like Aisha Asamusa.

To this end, the JDC is supporting the collection and analysis of socioeconomic data in around 30 conflict affected countries including Uganda, Central African Republic and Colombia. In these three countries, data has guided policy and programs that support forcibly displaced people. Removed from conflict, these people need development, and not just humanitarian aid. Socioeconomic data provides development actors and governments with the evidence they need to create programs and policies that are sustainable over the long-term.

The data produced by the FDS is aligned with international standards, making it comparable across countries and over time. It is the first time that UNHCR has produced this kind of data and, as such, it is a major step in providing the organization, its partners, governments and development organizations with the data they need to plan for people affected by forced displacement in the future. In addition to data collection, we also build capacity within national government to collect their own data.

The JDC is proud to support UNHCR in developing and implementing the FDS in South Sudan, Cameroon and Pakistan to achieve this, and is fully committed to the vision behind it.

Aissatou (Aisha) Dicko

Head of the World Bank-UNHCR Joint Data Center on Forced Displacement